Consent for Routine Medical Care A Comprehensive Guide, Including What is the Age of Consent in Virginia

Minor consent laws are legal provisions that allow minors to make decisions about their healthcare without the need for parental or guardian approval. These laws are crucial in ensuring that minors, particularly those who are unaccompanied or homeless, have access to necessary medical care. The significance of these laws lies in their ability to provide minors with the autonomy to seek medical attention, thereby protecting their health and well-being. Understanding specific regulations, such as what is the age of consent in Virginia, is essential for comprehending the broader context of minor consent laws. In many cases, these laws can be life-saving, as they enable minors to receive timely medical interventions, including vaccinations, which are essential for preventing disease outbreaks.

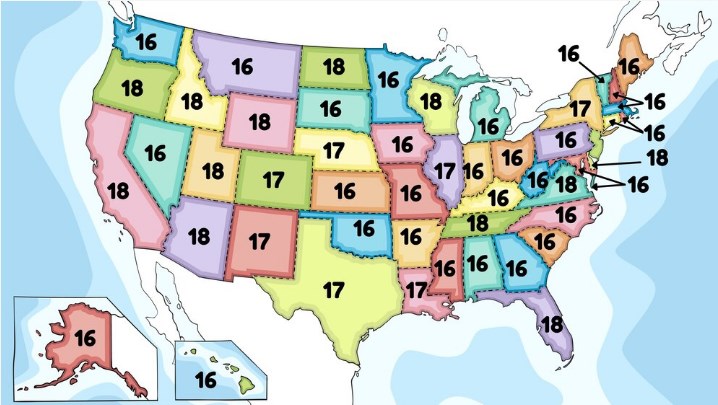

The primary purpose of this document is to provide a detailed analysis of how various states in the U.S. allow minors to consent to routine medical care. By examining the specific statutes and regulations in 35 states and the District of Columbia, this document aims to highlight the differences and commonalities in the legal landscape. Understanding these laws is particularly important during health crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, where timely medical care and vaccinations are crucial. This document serves as a resource for policymakers, healthcare providers, and advocates who work with unaccompanied and homeless minors, ensuring they are informed about the legal provisions that can help these vulnerable populations access necessary healthcare services.

This document covers the statutes and regulations of 35 states and the District of Columbia concerning minor consent for routine medical care. It specifically focuses on laws that allow minors living independently or those experiencing homelessness to consent to healthcare services, including vaccinations. However, the document does not address all aspects of minor consent laws. It excludes laws related to reproductive health, substance abuse treatment, mental health services, and sexually transmitted diseases. Additionally, it does not cover laws applicable to minors who are married, pregnant, or in the military, nor does it delve into court cases related to the “mature minor doctrine.” This document is intended to provide a comprehensive overview but is not a substitute for professional legal advice.

I. Summary of Laws by State

This section provides a detailed summary of state laws concerning minor consent for routine medical care and infectious disease treatment. Each state has its own specific statutes that govern the ability of minors to consent to medical care without the need for parental approval, particularly for those minors who are unaccompanied or experiencing homelessness.

A. Alabama

In Alabama, minors aged 14 and older, those who have graduated from high school, are married, divorced, or pregnant, can consent to any medical, dental, health, or mental health services for themselves without needing parental consent (Ala. Code §§22-8-4; 22-8-7). Additionally, any minor can consent to medical services for pregnancy, venereal disease, drug dependency, alcohol toxicity, or any reportable disease, including COVID-19 (Ala. Code § 22-8-6).

B. Alaska

Alaska allows minors living apart from their parents and managing their own financial affairs to consent to medical or dental services (Alaska Stat. §25.20.025). However, there are no specific provisions for infectious disease treatment for minors.

C. Arizona

In Arizona, any emancipated minor, minor who has contracted a lawful marriage, or homeless minor can consent to hospital, medical, and surgical care without the need for parental consent (Ariz. Rev. Stat. §44-132). Infectious disease treatment provisions are not explicitly stated.

D. Arkansas

Arkansas permits minors of sufficient intelligence to understand the consequences of medical treatment to consent to surgical or medical procedures (Ark. Code §20-9-602(7)). There are no specific provisions for infectious disease treatment.

E. California

In California, minors aged 15 and older who are living apart from their parents and managing their own financial affairs can consent to their own medical care (Cal. Fam. Code §6922). For infectious diseases, minors aged 12 and older who may have come into contact with an infectious disease can consent to medical care for diagnosis or treatment (Cal. Fam. Code §6926).

F. Colorado

Colorado allows minors aged 14 and older who are living apart from their parents and managing their own financial affairs to consent to medical, dental, emergency health, and surgical care (Colo. Rev. Stat. §13-22-103). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

G. Delaware

In Delaware, minors can consent to medical treatment if it is deemed necessary by medical professionals (Del. Code §707). Minors aged 12 and older can consent to treatment for contagious, infectious, or communicable diseases (Del. Code §710).

H. District of Columbia

In the District of Columbia, minors aged 11 and older can consent to vaccinations recommended by the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (Law L23-0193, effective Mar. 16, 2021). There are no specific provisions for other infectious diseases.

I. Florida

Florida law allows unaccompanied homeless youth aged 16 and older to consent to medical, dental, psychological, substance abuse, and surgical diagnosis and treatment (Fla. Stat. §743.067). There are no specific provisions for infectious diseases.

J. Hawaii

Hawaii permits minors aged 14 and older, who are not under the care of a parent, custodian, or legal guardian, to consent to primary medical care if they understand the risks and benefits (Hawaii Rev. Stat. §§577D-2, 577D-1). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

K. Idaho

Idaho allows any person who understands the need, nature, and risks of medical treatment to consent to it, including minors (Idaho Code §39-4503). Minors aged 14 and older can consent to medical care for infectious diseases if required by law to be reported (Idaho Code §39-3801).

L. Illinois

In Illinois, minors can consent to primary care services if identified as a “minor seeking care” by certain professionals and meeting specific criteria (Ill. Stat. §410.210/1.5). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

M. Indiana

Indiana allows minors aged 14 and older, who are living apart from their parents and managing their own affairs, to consent to their own health care (Ind. Code §16-36-1-3). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

N. Kansas

Kansas law permits minors aged 16 and older to consent to hospital, medical, or surgical treatment when no parent or guardian is available (Kan. Stat. §38-123b). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

O. Louisiana

Louisiana allows minors who believe themselves to be afflicted with an illness or disease to consent to medical or surgical care as if they were of legal age (Louisiana Rev. Stat. §40:1079.1). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

P. Maine

Maine permits minors living separately from their parents and independent of parental support to consent to medical, mental, dental, and other health services (Me. Rev. Stat. §22:1503). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

Q. Maryland

Maryland allows minors living apart from their parents and self-supporting to consent to medical or dental treatment (Md. Code §20-102). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

R. Massachusetts

In Massachusetts, minors can consent to medical or dental care if they are living apart from their parents and managing their own financial affairs (Mass. Gen. Laws §112:12F). They can also consent to care for infectious diseases that are dangerous to public health (Mass. Gen. Laws §112:12F).

S. Minnesota

Minnesota permits minors living apart from their parents and managing their own financial affairs to consent to personal medical, dental, mental, and other health services (Minn. Stat. §144.341). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

T. Missouri

Missouri law allows minors aged 16 or 17 who are homeless or victims of domestic violence and self-supporting to consent to medical care (Rev. Stat. Mo. §431.056). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

U. Montana

Montana permits minors who are living apart from their parents and self-supporting to consent to health services (Mont. Code §41-1-402). Minors can also consent to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of reportable communicable diseases (Mont. Code §41-1-402).

V. Nevada

Nevada allows minors living apart from their parents for at least four months to consent to medical treatment if they understand its nature and purpose (Nev. Rev. Stat. §129.030). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

W. New Mexico

New Mexico permits minors aged 14 and older living apart from their parents or guardians to consent to medically necessary health care (N.M. Stat. §24-7A-6.2). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

X. New York

New York allows runaway and homeless youth under 18 receiving approved crisis or support services to consent to medical, dental, health, and hospital services (A09604 Amd §2504, Pub Health L). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

Y. North Carolina

North Carolina law allows minors to consent to medical health services for venereal disease, pregnancy, controlled substance or alcohol abuse, and emotional disturbance (N.C.G.S.A. §90-21.5). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

Z. North Dakota

North Dakota permits unaccompanied homeless minors aged 14 and older to consent to medical, dental, or behavioral health examinations, care, or treatment without parental consent (SB 2265, 2021). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

AA. Oklahoma

Oklahoma allows minors separated from their parents to consent to medical services (Okl. Stat. §63-2602). They can also consent to the diagnosis and treatment of reportable communicable diseases (Okl. Stat. §63-2602).

BB. Oregon

In Oregon, minors aged 15 and older can consent to hospital, medical, or surgical diagnosis or treatment (Or. Rev. Stat. §109.640). Minors aged 15-17 can consent to COVID-19 vaccinations without parental consent (Or. Ad. Code 333-003-5000).

CC. Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania allows medical, dental, and health services to be rendered to minors without parental consent when delaying treatment would increase risk to the minor’s life or health (Penn. Stat. §35-10104). Minors can also consent to diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted and other reportable diseases (Pa. Code §27.97).

DD. Rhode Island

Rhode Island permits minors aged 16 and older or those who are married to consent to routine emergency medical or surgical care (R.I. Gen. Laws §23-4-16). Minors under 18 can consent to testing, examination, and treatment for reportable communicable diseases (R.I. Gen. Laws §23-8-1.1).

EE. South Carolina

South Carolina allows health services to be rendered to minors without parental consent when necessary, unless involving an operation essential to the child’s health or life (S.C. Code Ann. §44-29-90). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

FF. South Dakota

South Dakota permits minors to consent to medical care (S.D. Codified Laws § 13-28-7). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

GG. Tennessee

Tennessee allows minors to consent to medical, dental, psychological, and surgical treatment if they are aged 16 or older and living apart from their parents and managing their own financial affairs (Tenn. Code Ann. §68-1-120). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

HH. Texas

Texas permits minors aged 16 and older who are living apart from their parents and managing their own financial affairs to consent to medical, dental, psychological, and surgical treatment (Tex. Fam. Code §32.003). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

II. Utah

Utah allows unaccompanied homeless minors aged 15 and older to consent to any health care not prohibited by law (Utah Code Ann. §78B-3-406). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

JJ. Vermont

Vermont permits minors living apart from their parents and managing their own financial affairs to consent to medical treatment (Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 18, § 8704). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addr

essed.

KK. Virginia

Virginia allows minors to consent to medical or health services for birth control, pregnancy, family planning, substance abuse, mental illness, and infectious or contagious diseases that the State Board of Health requires to be reported (Va. Code Ann. §32.1-46). This includes services for the diagnosis and treatment of venereal diseases.

LL. Washington

Washington permits informed consent for health care for minors from school nurses, counselors, or homeless student liaisons when necessary for nonemergency outpatient primary care services (Wash. Rev. Code § 7.70.040). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

MM. West Virginia

West Virginia allows minors to consent to health care treatment if they are living apart from their parents and managing their own affairs (W. Va. Code §16-4-1). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

NN. Wisconsin

Wisconsin permits minors to consent to health care treatment to the same extent as an adult when living apart from their parents and managing their own affairs (Wis. Stat. §48.375). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

OO. Wyoming

Wyoming allows minors living apart from their parents a

nd managing their own affairs to consent to health care treatment (Wyo. Stat. §14-2-102). Infectious disease treatment is not specifically addressed.

This comprehensive summary of state laws demonstrates the varied approaches to minor consent for medical care and highlights the critical need for awareness and advocacy to ensure unaccompanied and homeless minors receive the health care they need.

II. Analysis and Discussion

A. Common Themes and Variations

In analyzing the state laws on minor consent for routine medical care and infectious disease treatment, several common themes and variations emerge. A prevalent commonality is that many states permit minors who are living independently or are unaccompanied to consent to their own healthcare. This autonomy is particularly emphasized for minors aged 14 and above, a threshold seen in states like Alabama, Idaho, and Illinois. These laws typically cover routine medical care, including vaccinations and emergency health services, reflecting a widespread recognition of the necessity for minors to have access to healthcare regardless of parental involvement.

However, significant variations exist in the specifics of legal requirements and the scope of consent. For instance, while California and Colorado both allow minors aged 15 and older to consent to medical care if they are managing their own financial affairs, the exact nature of what constitutes “managing financial affairs” can vary. Additionally, some states, like Massachusetts and Montana, include provisions for minors to consent to treatment for infectious diseases, such as sexually transmitted infections, while others do not explicitly address infectious diseases within their statutes.

Another notable variation is the range of documentation required to establish a minor’s eligibility to consent. In some states, a simple self-declaration of independent living status is sufficient, whereas others, such as Missouri and Texas, require more formal documentation, including letters from social workers or legal representatives. These differences highlight the diverse approaches states take to balance minor autonomy with safeguarding against potential abuses or misunderstandings.

B. Impact of Laws on Unaccompanied Minors

The impact of these laws on unaccompanied minors is profound, especially in emergency situations like pandemics. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the ability for minors to consent to their own healthcare, including vaccinations, became critically important. States with clear provisions allowing minor consent without parental involvement were better positioned to ensure these vulnerable populations received necessary medical attention promptly. For instance, the District of Columbia’s law enabling minors as young as 11 to consent to vaccinations recommended by the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices ensured that many minors could be vaccinated against COVID-19 without delay.

However, in states without explicit provisions for infectious disease treatment, unaccompanied minors faced significant barriers. The lack of legal clarity often resulted in minors being unable to receive timely testing and treatment for COVID-19, exacerbating public health risks. This discrepancy underscores the need for comprehensive and inclusive minor consent laws that address a broad range of health scenarios, ensuring that unaccompanied minors are not left without essential healthcare during critical times.

C. Practical Implications

In practice, the application of these laws by healthcare providers and social services reveals both successes and challenges. Healthcare providers in states with robust minor consent laws report higher engagement from minors seeking care independently, leading to better health outcomes. However, practical challenges remain, particularly in states with ambiguous or restrictive consent laws.

One significant challenge is the variability in interpretation and implementation of the laws. Healthcare providers must often navigate complex legal landscapes, which can result in inconsistent application of the laws. In states requiring documentation for minors to prove their eligibility, the burden often falls on social services to provide the necessary verification, which can delay care. Additionally, the stigma and lack of awareness around these laws can prevent minors from seeking the care they need.

Barriers to implementation also include logistical issues such as lack of access to healthcare facilities, financial constraints, and administrative hurdles. These challenges highlight the need for improved training for healthcare providers and social service workers on minor consent laws, as well as streamlined processes for verifying eligibility and providing care.

In conclusion, while state laws on minor consent for routine medical care and infectious disease treatment generally aim to support the autonomy and health of unaccompanied minors, there is considerable variation in their scope and application. Addressing these variations and overcoming practical challenges are essential steps toward ensuring that all minors have equitable access to necessary healthcare services.

III. Legal and Policy Considerations

A. Legal Challenges and Conflicts

The implementation of minor consent laws for routine medical care and infectious disease treatment has not been without legal challenges and conflicts. One of the primary legal challenges arises from the varying interpretations of what constitutes a minor’s capacity to consent. States like California and Colorado, which permit minors living independently to consent to their own healthcare, often face legal scrutiny regarding the assessment of a minor’s financial independence and decision-making capacity. Courts in these states occasionally see cases challenging whether a minor truly meets the criteria for independence, leading to legal disputes that can delay care.

Another significant legal conflict involves the intersection of state and federal laws. For instance, while some states allow minors to consent to medical care, federal regulations like the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) can create confusion about minors’ rights to privacy and access to their own medical records. Inconsistent applications of HIPAA regulations across different healthcare providers can result in breaches of confidentiality or denial of access to necessary medical information for minors.

Additionally, parental rights groups have occasionally challenged minor consent laws, arguing that they infringe upon the parents’ right to be involved in their children’s healthcare decisions. These groups assert that parents should have a say in significant medical decisions, and as a result, some states have faced pressure to amend or repeal minor consent laws. These legal battles highlight the tension between protecting minors’ autonomy and respecting parental rights.

B. Policy Recommendations

To improve the implementation and accessibility of minor consent laws, several policy recommendations can be considered. Firstly, states should standardize the criteria for determining a minor’s capacity to consent. This standardization can be achieved through clear guidelines and checklists that healthcare providers can use to assess a minor’s financial independence and understanding of medical decisions. By creating a uniform assessment process, states can reduce legal ambiguities and ensure more consistent application of the laws.

Secondly, education and training for healthcare providers and social workers are crucial. These professionals need comprehensive training on the legal aspects of minor consent, including understanding state-specific laws and federal regulations like HIPAA. Providing ongoing education will help ensure that healthcare providers can confidently navigate the legal landscape and offer the necessary care to minors.

Another recommendation is to streamline the documentation process required for minors to prove their eligibility to consent. States like Missouri and Texas require formal documentation from social workers or legal representatives, which can create barriers. Simplifying these requirements and allowing for alternative forms of verification, such as self-attestation or support letters from community organizations, can enhance access to healthcare for minors.

Furthermore, raising public awareness about minor consent laws is essential. Many minors and their guardians are unaware of the legal provisions that allow them to seek medical care independently. Public awareness campaigns, school-based education programs, and informational resources provided by healthcare facilities can help inform minors of their rights and encourage them to seek necessary care without hesitation.

Recommendations for future legislation should focus on addressing gaps and inconsistencies in existing laws. For example, expanding the scope of minor consent laws to explicitly include infectious disease treatment in all states can ensure that minors have access to timely care during public health emergencies. Additionally, incorporating mental health services and reproductive health into minor consent laws can provide comprehensive healthcare access for minors.

Legislators should also consider the benefits of adopting the “mature minor doctrine” universally. This doctrine, which allows minors deemed mature enough to understand the consequences of their medical decisions to consent to care, can offer a flexible and pragmatic approach to minor consent. By adopting this doctrine, states can provide healthcare access to minors who may not fit traditional criteria but demonstrate the necessary maturity to make informed decisions.

In conclusion, addressing the legal challenges and conflicts related to minor consent laws requires a multifaceted approach. Standardizing assessment criteria, providing education and training, streamlining documentation processes, raising public awareness, and enacting comprehensive legislation are essential steps to ensure that all minors have equitable access to necessary healthcare services.

The analysis of state laws on minor consent for routine medical care and infectious disease treatment reveals a complex and varied legal landscape. Common themes include the widespread allowance for minors living independently to consent to their own healthcare and significant variations in the specifics of these laws across states. Some states require detailed documentation and formal verification, while others rely on self-declaration. These laws are crucial in ensuring that unaccompanied minors, particularly those experiencing homelessness, have access to essential healthcare services. However, inconsistencies and gaps in the laws pose challenges for healthcare providers and minors alike.

Awareness and advocacy play a vital role in ensuring that unaccompanied minors receive the healthcare they need. Public awareness campaigns, educational programs, and resources provided by healthcare facilities can help inform minors and their guardians of their rights under minor consent laws, including what is the age of consent in Virginia. Advocacy efforts are essential in pushing for legislative changes to address gaps and inconsistencies, ensuring that all minors, regardless of their living situation, have access to comprehensive healthcare. Advocates can also work to streamline documentation processes and promote the adoption of the ‘mature minor doctrine’ to enhance healthcare access for minors who demonstrate the necessary maturity to make informed decisions.

Minor consent laws are critical in safeguarding the health and well-being of unaccompanie

d and homeless minors. These laws empower minors to seek necessary medical care without parental involvement, providing a safety net for vulnerable populations. However, the varied and sometimes ambiguous nature of these laws necessitates ongoing efforts to standardize and improve their implementation. By raising awareness, advocating for policy changes, and providing education and training for healthcare providers, we can ensure that minor consent laws effectively serve their intended purpose. Ultimately, these efforts will contribute to a more equitable healthcare system that addresses the needs of all minors, protecting their health and fostering their overall well-being.

Age -Navigating the Complexities of Consent Washington Age of Consent, Sexting, and Legal Implications

Understanding Sexual Consent Laws and the Virginia Legal Age of Consent in the Commonwealth

Travis bagent’s age “The Beast” The Unstoppable Force in Arm-Wrestling’s History and His Age

A Comprehensive Look at the Model’s Career, Impact, and Nikki Howard Age

Essential Laws Every Tourist Should Know, Including the Legal Drinking Age in Cancun, Mexico

Ashley Cruger Kinney A Journey from Journalism Graduate to Model and Business Development Manager – Exploring Ashley Cruger Age

Understanding Age of Sexual Consent in Maryland A Comprehensive Analysis of Age of Consent Laws

| Sitemap | Mail

| Sitemap | Mail